An introduction to the Indigenous People (PA) of Congo

This change is more than semantic—it represents a reassertion of dignity, cultural sovereignty, and a deep-rooted connection to nature that has guided their way of life for millennia.

Traditional Culture and Way of Life

Historically, the PA composed of indigenous groups such as the Mbuti, Aka, and Twa of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, have lived as skilled hunter-gatherers. Although each tribe possesses its own languages, customs, and social structures, all tribes exhibit a profound respect for nature.

Their survival depended on a profound and intricate understanding of the rainforest’s biodiversity. Every element of their existence—from tracking wildlife and foraging for medicinal plants to the rhythmic cycles of seasonal change—is interwoven with the natural world. This intimate knowledge is not only practical but also deeply spiritual. Their rituals, music, dance, and oral traditions reflect a worldview that venerates the forest as a living, nurturing force and underscores the importance of balance and reciprocity in nature.

History, Marginalization, and Resilience

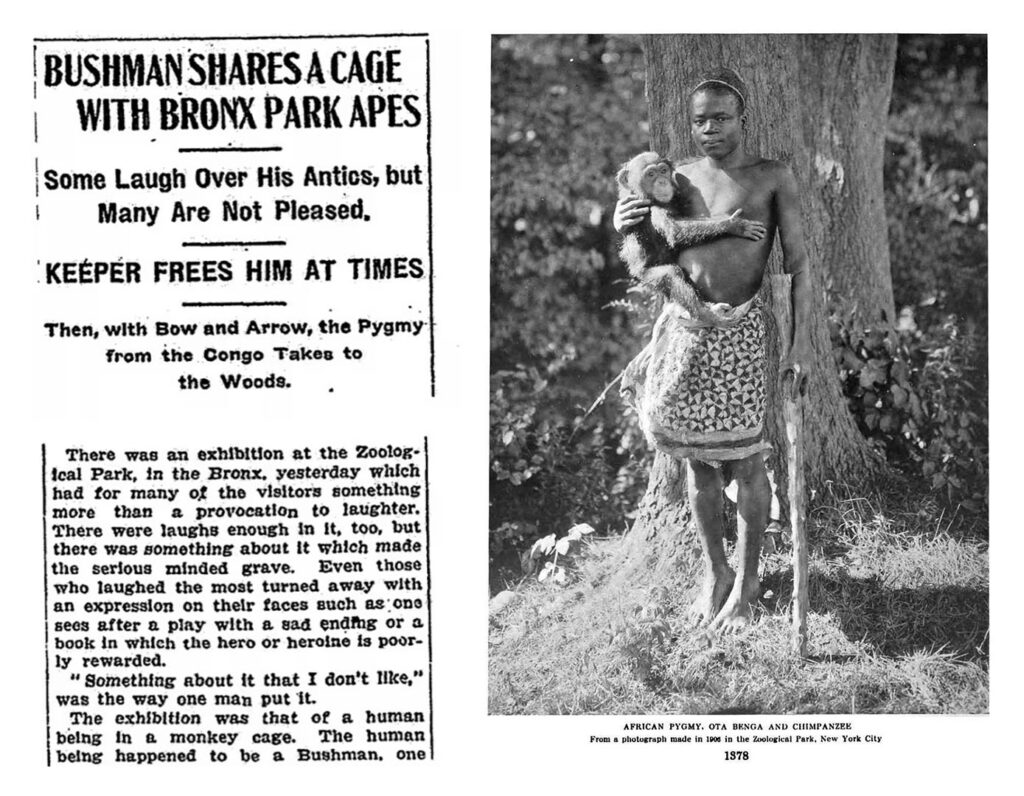

Despite their rich cultural heritage, the PA have long faced marginalization and exploitation. Colonization, forced labor, and displacement have all left enduring scars. In 1904, Ota Benga was kidnapped from Congo and taken to the US, where he was exhibited with monkeys. His appalling story reveals the roots of a racial prejudice that still haunts us. In the post-independence era, these challenges have persisted. Social and economic exclusion, discrimination, and encroachment on their ancestral lands have undermined their ability to maintain traditional lifestyles.

Logging, mining, and agricultural expansion continue to erode the forest, threatening both the environment and also the foundation of cultural and economic practices of PA (Hewlett, 1991; Bahuchet, 1998). Habitat destruction and loss of biodiversity disrupts the delicate ecosystem but also undermines PA traditional lifestyle, forcing many to abandon their nomadic paths for sedentary life in nearby villages.

A future where innovation and nature thrive hand in hand

Today, as the world confronts unprecedented environmental challenges amid rapid technological change, PA knowledge stands as a treasure trove of sustainable practices and insights into native plants, animals, minerals, and medicines. This extensive ecological wisdom, passed down through generations, offers practical guidance for rewilding efforts. Rewilding—restoring natural processes, reintroducing keystone species, and promoting natural regeneration—is essential for rebuilding biodiversity and strengthening ecosystem resilience. By reestablishing critical functions like nutrient cycling and predator-prey dynamics, rewilding also enhances ecosystem services such as clean water, carbon storage, and soil fertility.

Suding et al. (2015) emphasize that rewilding is a crucial strategy for combating environmental degradation and mitigating climate change, underscoring its importance for global conservation.

Building on these insights, envision a future where renewable energy systems, urban planning, and conservation strategies are enriched by indigenous perspectives. Guided by traditional ecological knowledge, engineers could design technologies that replicate natural cycles, while policymakers craft economic frameworks that prioritize environmental stewardship and community well-being. This synthesis offers pathways to economic development that are both innovative and ecologically sound, ensuring progress without sacrificing the planet’s health (Berkes, 2012).

Moreover, modern innovation can empower the PA by equipping them with tools and platforms that amplify their traditional practices and strengthen their voice in global environmental conversations.

Advanced communication and mapping technologies can help document and preserve their ecological insights, and sustainable energy solutions can bolster community-led development without compromising indigenous lifestyles. Together, this integrated approach harnesses the power of traditional knowledge to address contemporary environmental challenges and build resilience in a rapidly changing world—a future where innovation and nature thrive hand in hand.

By valuing and incorporating indigenous perspectives, modern societies can gain insights into sustainable living practices, regenerative biodiversity, and the ethical treatment of natural resources. At the same time, modern innovation equips indigenous communities with advanced tools and platforms to document, share, and enhance their knowledge, enabling them to better protect their lands, assert their rights, and preserve their heritage.

References

- Azote for Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University. Based on Richardson et al. 2023, Steffen et al. 2015, and Rockström et al. 2009.

- Newkirk, P. (2015). The man who was caged in a zoo, The Guardian

- Bahuchet, L. (1998). Central African Pygmies in Context: Polity, Economy, and Society. Berg Publishers.

- Berkes, F. (2012). Sacred Ecology (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Hewlett, B. S. (1991). Hunter-Gatherers of the Congo Basin: Cultures, Histories, and Evolution of African Pygmies. Cambridge University Press.

- Woodburn, J. (1996). Mbuti Pygmies and the Conservation of Tropical Forest: An Enduring Link. [Journal/Publisher details, if available].